SETTING AS CHARACTER

I am hooked by immersive world building. When I pick up a book and the author has the ability to transport me to another time and place, I will become so invested in the story that time floats away. It’s the thing I love most about reading historical fiction and fantasy. But when the world building goes deeper—when the author uses the setting as an actual character that you can almost see and hear from the page, well—that’s a hallmark of Gothic fiction that I find absolutely irresistible.

Here’s an example from Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca:

“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again. It seemed to me I stood by the iron gate leading to the drive, and for a while I could not enter, for the way was barred to me. There was a padlock and chain upon the gate. I called in my dream to the lodge-keeper, and had no answer, and peering closer through the rusted spoke of the gate I saw that the lodge was uninhabited.”

The first line of Rebecca is often quoted, but the entirety of the opening is spent on setting up the atmosphere of the novel. While she veers toward an excess of exposition, du Maurier keeps things from becoming staid and boring by leaning into the nameless main character’s feelings and interiority. We are in her head, with her eyes as our lens, fixed on the world she’s returned to in her dreams. Manderley looms over it all—beautiful and terrible and haunted by the past.

Rebecca was a huge influence on Parting The Veil. When Eliza comes to England to claim her inherited estate, she has a similar experience upon arrival. Only…her house isn't the one that’s haunted. It’s the house next door

Haunted houses are a recurring element in Gothic fiction. I never tire of them. A recent favorite, It Will Just Be Us by Jo Kaplan, takes the haunted house trope and twists it masterfully. The rambling ancestral home Sam Wakefield shares with her eccentric mother is haunted by ghostly memories trapped in time. When her pregnant sister moves home after a fight with her abusive husband, the atmosphere in the once-grand mansion becomes rife with tension.

Sam’s anxiety over the disturbing new visions she sees of a faceless boy haunting Wakefield’s labyrinthine halls sets her on a mission to unravel the mystery hidden within a locked, forgotten room inside the house before her sister brings new life into the world. Built at the edge of a fetid swamp, Wakefield is marked by death and the horrors of the past. The decayed setting exacerbates the torn loyalties within Sam’s family and the creeping dread symbolized by the encroaching swamp.

“The swamp, shrouded in heavy mists and the odors of decay that conceal lurking predators and invisible quicksand, should warn us all to stay away. This is a bad place, the swamp communicates to us. Do not enter. So what is that voice underneath the warning, entreating us to see it for ourselves? What is this siren song of the swamp?”

It Will Just Be Us is simply a masterpiece. I don’t say that about many books, but from the first few lines, I knew I’d discovered a story I could really sink my teeth into. Kaplan’s lyrical prose is darkly beautiful and harrowing. Her plot unspools and beckons the reader forward, culminating in a shocking twist.

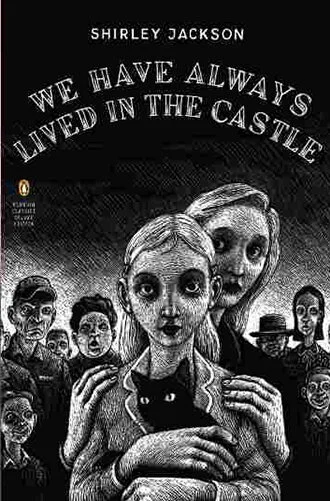

Shirley Jackson is often lauded for The Haunting of Hill House, which is understandable. But one of her smaller, lesser-known works has remained a personal favorite for many years. We Have Always Lived In The Castle is a slim volume, but it packs a lot of clever surprises within its slight pages.

After a family tragedy, Merricat and her older sister Constance have become outcasts and pariahs in the small village they inhabit. There are whispers of witchcraft and murder, and the Blackwood sisters are the subjects of gossip and conjecture. They shut themselves away behind the walls of Blackwood with their oddball Uncle Julian, protected by Merricat’s magical thinking and childlike spells. Merricat dreads going to town because of the constant bullying she faces:

“I remember that I stood on the library steps holding my books and looking for a minute at the soft hinted green in the branches against the sky and wishing, as I always did, that I could walk home across the sky instead of through the village. From the library steps I could cross to the grocery, but that meant that I must pass the general store and the men sitting in front. In this village the men stayed young and did the gossiping and the women aged with grey evil weariness and stood silently waiting for the men to get up and come home.”

The village in We Have Always Lived In The Castle, with its cloying, superstitious misogyny, helped inspire the small Ozarks town in my current work-in-progress. Anyone who has ever lived in a small town is familiar with the kind of social claustrophobia Merricat experiences. It comes from living in a place where everyone knows who you are—and what they think you’ve done. For all their supposed apple pie wholesomeness, small towns can be extremely unfriendly…especially if you are different.

Settings with harsh, unforgiving elements are also at work in two recent novels I’ve read, both set in the Scottish Highlands. In The Turn Of The Key, Ruth Ware takes the classic tropes in Henry James’s The Turn Of The Screw and cunningly twists them to include our own modern-day horror: technology. Her setting, a recently renovated smart home, is a shining example of setting as character. From the moment our protagonist—an ambitious nanny from the city—arrives, we know something is wrong with this house.

“Instantly something felt off-kilter. But what was it? The door in front of me was traditional enough, paneled wood painted a rich glossy black, but something seemed wrong, missing, even. It took me a second to notice what it was. There was no keyhole. The realization was somehow unsettling.”

From the lights and curtains that seem to have a mind of their own, to the deadly poison garden on the estate’s grounds, Ware crafts an almost sentient monstrosity of a house haunted by humanity’s hubris. The hype for this book is well-warranted.

Francine Toon’s Pine is a gritty, surrealistic modern Gothic with quiet moments in the beginning and a second half that clips along at a breakneck pace. Mixing elements of Scottish folklore with the story of a family haunted by grief and regret, Toon doesn’t shy away from exposing the hypocrisies of the characters inhabiting her small town. Nor does she downplay the beautiful but unforgiving environment of the Highlands, where the winter night descends by early afternoon, and dense forests of pine conceal old sins unforgotten. I’m still thinking about this book weeks after reading. Toon deftly weaves the supernatural elements throughout, and her world building is so brilliant I could hear the crunch of Niall’s boots on the freshly-fallen snow:

“Niall is walking through pitch black, the crunch of ice and rocks beneath his feet, the smell of the pine fresh and frosty, heavy with snow. He knows he is getting closer to the centre of the forest and knows he shouldn’t be there.”

My only complaint about Pine is that I wished it had been longer. It’s as beautiful and piercingly sharp as a January icicle sliding from a roof.

While these are but a few of my favorites that feature settings as character, there are many others within the canon. Whether it’s an isolated outpost in Scotland, a manor on a lonely hill, or a desolate swamp, there are myriad ways writers can give presence and depth to their stories through the use of setting. I’d love to hear some of your favorite examples in the comments!

(Buy links for the books mentioned are hyperlinked within)